Not so Big?

Not so Smart!

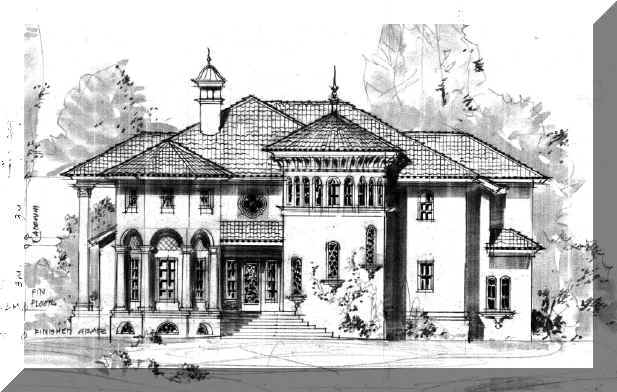

Ultra Luxury Custom Homes, Villas and Estates by design

Interested home buyers, Architects

and Builders should become quickly aware of the ramifications of designing and

building "Not so Big" (NSB). The

term has connotations of environmentalism and universality, which may be why

little or no critical response has challenged the tenets to date.

While obviously not a new concept, its base appeal is gaining popularity

and creating expectations that one can afford to design and build a

substantially better home by merely cutting out relatively inexpensive

floor area and dedicating it to upgrades, additional trim, better quality doors/

windows, etc. The consumer should

understand that the added costs for building Not So Big are typical of any

custom design project, and can raise the soft and hard costs to double or triple

for the work required to fulfill their wish list.

A NSB house then is basically a fully detailed

project that is ultra customized for a relatively smaller home than would be

built for that budget otherwise. The

concept was developed as a result of allegations by architect Sarah Susanka that

the existing system is designed to offer consumers only larger, less

detailed and out of scale houses -- houses that simply do not have any real

architectural character and have unnecessary wasted and normally unusable

spaces. These mcmansions have

unsightly exteriors while offering ill proportioned and merchandised interiors

that do not respond to an unserved market segment requiring better detailed and

built homes. She contends that

potential homeowners have few options in terms of cost/ value and that the

market is leading the consumer to build bigger but not better.

Ms. Susanka also believes that most people do not understand that

architects are actually charged with designing houses (among other building

types) rather than builders. She

is championing an awareness of the design professional as primary in the home

design process. Her proof that her

assessments have struck a deep felt chord is mainly evident in the number of

requests for smaller, but highly detailed and more imaginatively conceived

houses her firm and others connected with her program have received after

publication of her two seminal books, and the call for personal seminars from

various parts of the country to hear her speak.

Newest on her agenda is a holistic approach to designing the built

environment that will probably address suburban sprawl, while appealing to green

building, feng shui, etc. to cure the ills of the world.

The idea of building smaller but better is not a new one.

Anyone contemplating construction must meet the same issues of size

versus quality at the very beginning. Budget

is discussed at initial meetings with an architect or builder and the question

is immediately raised concerning space in relationship to quality of finishes,

materials selection, style and size of home.

Building professionals must constantly advise their clients with cost

estimates based on outline specifications at the beginning before proceeding

with design schematics and until complete specifications are issued.

The question as to how much smaller does one have to

build in order to make the final result better in terms of design and

quality is complex and is dependent on the skill of the architect, the

capabilities of the builder, the availability and transport of materials, and

the experience of the trades and subcontractors.

But by embracing this carefully crafted statement, potential custom home

clients assume that it is a relatively simple trade-off:

This is the art of the Not So Big

House: to take out square footage that's seldom used, so that you can

put the money saved into the detail, craft, and character that will make

it eminently comfortable and uniquely yours.

In short, it favors quality over quantity.

The idea is compelling but the practicalities are flawed. For openers: how can you plan for a house if you know you should take out 30% of it before starting to plan for your house? What Zen! And doesn't this reasoning remind one of a similar argument made by many builders to the potential client: Select one of the pre-designed plans from our portfolio and "customize" it. Cut out the architect fees and put it into quality finishes or a bonus room.

Building professionals know that this sleight of hand just doesn't add up. It is a recurring reality that the wish list (basic requirements in terms of number of rooms, circulation, storage, etc. organized in a fashion that will have spirit and a style of its own), when translated in cost per square foot typically exceeds initial budget estimates. The client is overjoyed at the initial drawings that fulfill the program, but know that he must cut back somewhere in order to meet budget.

The first attempt to solve this problem is to cut some of the rooms down in size. This is a gut-wrenching procedure that seems unavoidable. The second step is to eliminate one or two rooms, which invariably induces near cardiac arrest. But for some reason budget is still exceeded. The answer is simple: one cannot cut out empty rooms alone and expect substantial savings. One has to reduce the quality of materials and finishes, perhaps lower ceiling heights and roof pitches, opt for less expensive cabinets and counter tops, architectural trim, etc. in order to meet budget.

There is no straight-line correlation between cutting overall living area in order to put savings into quality of space. The extra goodies Susanka offers up cannot be had by cutting raw space (living area square footage) alone. The budget must increase as well. In other words, taking out 1000 square feet from a 6,000 square foot house priced at $100/ SF (without lot costs), a 16.7% decrease in overall living area, will certainly not allow one to put $100 grand into general upgrading.

This point is well understood in the industry but confounds the consumer: if one keeps the basic elements of a house intact stock cabinets, plumbing and electrical fixtures, windows, doors, AC and heating system, TV/ media/computer connections, etc-- and simply cuts out the formal Living Room, extra bedroom, exercise room, etc. cost savings (in the above example) is at best only $25-50/ SF. Cutting out the elbowroom and extra spaces of a house may save on energy costs at best, and will buy some upgrades yes, but not nearly how much is implied by the Not So Big approach. At the worst, eliminating unused spaces and rooms may make a house feel cramped and less marketable at resale compared to its bigger but potentially less detailed brethren. And how can you possibly cut out one third of a much smaller house anyway without seriously affecting livability?

Imagine this scenario. A potential client meets with a building professional for the first time and claims -- "I have been thinking about building about 3,000 square feet for my family. We have three kids and would like a three bedroom, two-bath home with a formal living/ dining, kitchen open to a family room and breakfast area. If you can squeeze in a study we would be thrilled, and another bath." The professional responds with this: "Well, you know that if you cut 1/3 of your house down we can offer you some tremendous spatial effects, upgraded cabinets, inspiring trim, wood windows instead of aluminum..." The typical homeowner would stare in disbelief, get blue in the face, bluster under his breath, and storm out.

Actually, if one double backs

two secondary bedrooms to a single bath, cuts on the upgrades in kitchens

(appliances, cabinets and counter tops), elects for a basic communications/

electronics system rather than the top of the line home automation

extravaganzas, specifies uniform trim and molding with just a few highlights,

selects medium quality flooring, etc. then house size can be appreciably

increased by a factor double that of the reverse-engineering Susanka proposes.

And this is what Americans elect to do, from starter to luxury homes.

The "Not so big" concept actually works

best for those with more money to spend, not less.

More simple space is much less expensive per square foot than more

detailed/quality space per square foot.

Mass production merchant builders offer up the best value for the smaller entry level, move up or empty nester home. This is done by building a fairly priced product through the economies of large-scale construction. Building "not so big" also involves a degree of customization that will require additional soft costs: "Achieving the degree of tailoring that she champions, however, requires the services of an architect and a custom builder." -- Katharine Salant, Inman News. By her own admission, Susanka's back to back "not so big" version of the basic home of the same size proposed in Life magazine's feature project a few years back, cost nearly twice as much!

The larger the home, the more a client is willing to invest in 'architecture', not the other way around. It is a numbers game: the merchant builders attempt to meet market demand. At this time more than ever before, there are home options for all demographics - condominiums, starter plans, empty nester designs, retirement homes, new urbanist houses, etc. You can be in a high-density urban setting or out in the suburbs. But the facts are that we are building bigger on the average.

Susanka blames the housing industry for leading the unknowing consumer into wasteful larger, less detailed homes (horrors!) and implies a dark conspiracy involving the financial cartel, materials suppliers, utilities providers, U.S. public policy, etc. This is patently absurd. American home buyers know exactly what they are getting into -- know that architects are available to design any whim they might have in mind, but prefer in overwhelming numbers to grab the largest home they can find in the best neighborhood possible at the best price usually erected by a merchant builder. Recent research (by Robert Frank, a Cornell University professor of economics, ethics, and public policy) proves that it is the ongoing behavior of our peers which ultimately determines how much we spend and how we spend it not ignorance, a national conspiracy, or Wall Street marketing hype.

The extra quality of life features opined by Susanka and other Arts and Crafts proponents (anti-classicists and modernists as well) simply cost much more than a space tradeoff. Such homes, which happen to be smaller as built at the turn of the century, were also built with an emphasis on hand work as a protest to machine production. Reactionaries to the Industrial Age, this movement could not withstand the increase of space required by families of all sizes and economic profiles that could only be offered in a Democratic capitalist society which depends on mass production to increase the quality of life for all.

Susanka challenges long-standing theories of space perception and cultural mores with such statements:

"With its tall ceilings and marble floors, it was designed to overwhelm and impress visitors, not to welcome."

"We

are all searching for home, but we are trying to find it by building more rooms

and more space. Instead of thinking

about the quality of the spaces we live in, we tend to focus on quantity. But a house is so much more than its size and volume, neither

of which has anything to do with comfort."

These and other like quips are patently false or misleading. Tall ceilings and marble floors work to impress and welcome. And so what if it is one and not another? Is this class war? Size and volume has as much to do with comfort as anything else. Her comment about floor plans is that "The "feel" (of a house) comes from the experience of our senses, not just from the route we take from one room to the next." The experience of moving through space certainly has an effect of our perception of it.

Susanka claims that it is wise to cut the formal (read: presumed excessive or unusable) spaces such as Dining and Living rooms in favor of directing that booty towards a smaller total living area with better details while making up with spatial trickery. Are formal living and dining areas completely useless or so infrequently used that they ought to be left out of a Not So Big House? Traditional formal areas provide transition space from the "outside" or public realm, to our inner sanctum, a well-developed tool for architectural spatial progression. A formal staircase, central to the house "practical and decorative, normally is situated in a large foyer. It offers up decorative detail and potent imagery. The typically situated formal rooms, for many people, have tremendous impact psychologically beyond being a 'comfortable' or "necessary" room. Depending on the region, they are an inbred tradition: they are part of a culture of graciousness, they are an expected feature, they provide at least one area in which to get away from otherwise "rustic" activities and yes, they offer a showcase for fine furniture/ antiques. Most importantly they make an opening statement about who we are. (The most endearing quality though may be that they originally allowed grown-ups to entertain and socialize with each other apart from the din of children screaming in the back rooms, something a "not so big" house cannot offer.)

Susanka offers basic design motifs that are routinely employed by large and small space

creators alike: "shelter around activity", double duty space, diagonal

views, change of ceiling heights, private and public space, perspective and

scale, etc. These are not new

revelations, just techniques often left out by the ignorant (or soon-to-be

bankrupt!) merchant builder it seems, but not by all builders and architects.

The astute custom or semi-custom builder will attempt to satisfy market

demand and hire the appropriate talent to deliver it.

"Hot buttons" in terms of creature comforts and specialty space

sells.

Susanka implies that all "larger" houses are ill designed and have no soul, a comment that also contains a tinge of class envy). She especially despises tall ceilings. Those who design, build and live in large(er) houses offer models for the smaller budget builder to emulate. Those who build larger can afford more intellectual and technically capable architects who take the art to exemplary heights while often breaking the status quo to test new concepts and reinterpret the past. These innovations are routinely adopted by smaller home builders. They typically look to large luxury homes for design elements that they can incorporate in other price points. And note this: those who build the avant garde or "modern" new concepts usually end up spending 2-5 times the cost of the conventionally constructed house.

If we stretch either point we have absurdity: either a tiny, cramped but nicely appointed house is better or one that is an out of scale pretentious marble barn with endless rooms. The fact is that both can be well proportioned and detailed to satisfy a great range of spatial experiences and gratify a smorgasbord of lifestyles with varying economic means. "Character" is not exclusive to size; it is how space and finishes are organized/ specified. Most architects concur:

Is it possible to think great thoughts in small(er) spaces? Most likely. Can larg(er) spaces be inspirational as well? No doubt. Is bigger better? Not always. Is smaller better? Not for everyone. And how do NSB houses look and work? Most of the examples are cleverly designed, well thought out homes that respond exactly to client needs and expectations it seems. But they also appear tight and inflexible. The explanation? "One of the most surprising aspects of building Not So Big is that the measurable dimensions are smaller, but the psychological dimensions are bigger."

The first impression one gets upon entering Ms. Susanka"s personal home, as illustrated in her book, is a blank wall immediately at the Foyer. Her not so big house, on the outside, consists of a two-car garage slamming into a narrow box of living area, not much different from the typical mid-west suburban "great room" tract house on a small lot. Yes, there are some attractive "craftsman-like" details in low ceilinged rooms, materials contrast, color work, and smart combined space use. Most of the not so big plans featured in Susanka"s books are situated in rural areas (avoiding the garage in your face malady) and appear small and crampy outside their central "everything open to each other" space, with narrow halls and passages, tight kitchens, occasional fixed seating, minimum baths, etc. providing little storage space and the ability to move furniture around or be able to "customize" rooms over time. In fact, some feel like mcHobbits versus the mcMansions she decries. They are static and obsessively designed to fulfill the unwavering initial mindset of the owners and architect. Of course it is difficult to offer flexibility in smaller space, but not multiple spaces. These not so big houses are extremely idiosyncratic; in short they are ultra-customized and would have severe resale consequences in a typical subdivision " which is probably why most are nestled away from one.

Homes with many rooms offer options to experience day-to-day tasks under different circumstances: the change of light and season, for example. It is revealing that the European villa type of the 16th century and later was constantly internally reorganized depending on the seasons. Dining and Living rooms were interchanged depending on breezes, lighting, views, prevailing temperatures, etc. How often does one wish to escape the monotonous fate of having to do everything in a limited space, over and over?

The drive towards larger, bigger-is-better, happens to be a national epidemic, er"characteristic. It is evident in everything we do -- how we build our cities, cars and roads, and where we live. Building more or bigger offers cost savings due to volume purchases and mass production. You can generally get more for your architect's fee and from your builder --as you can by buying in bulk-- by building bigger. In fact, most architects would charge more as a percentage of construction cost for a smaller design than a larger one. And if you have to situate your specialty home away from the immediate suburbs, your costs of construction will increase as well.

For better or worse, Americans

crave the freedom of larger rooms, larger houses, more land, bigger offices,

theaters, sports and recreational buildings, etc. The average livable area in new

homes is at a record high. From

1971 to 1998 the average American home grew over 40% from 1,520 SF to 2,190 Sf..

Builders and architects simply respond to the market.

What then makes for character in today"s homes? More often than not, and unfortunately so, "character" is what people are carrying around with them as they move up or down career/ job-wise from town to town. It not as evident in the physical house structure of our time as compared to houses built before WWII. We customize our interiors with our movable belongings and gadgetry. Our mobile nature and meager artistic schooling (of late) combine to yield this unfortunate cultural sandwich: we care little about fine art nor recognize the extra details that can make architectural ingenuity and embellishment add meaning or comfort to our lives. We would rather fill our air-conditioned homes with space-age, high-tech gadgets for entertainment, communications, and business, and, with our furniture/ accessories -- take these things with us every 2-5 years rather than throw surplus cash into architectural refinements. Our disposable housing mentality is reflected in how houses are built as well. We do not build heritage estates for our families or posterity because" we have condo mortgages to take care of and need to upgrade our cars every year or two!

If you can afford to build 'better' for the long term, fine, but we do not hold onto houses as long as we used to, therefore the adage: 'They don't build 'em like they used to'. In the end: we buy what we can afford or not, what we rationalize, how we wish to project ourselves (as far as luxury goods go -- and the Not So Big House is a luxury item!), and how we intimately wish to live behind our four walls.

Bottom line: we would all love, -- no, lust to have bigger homes in which to live. That appears to be our first priority when contemplating a new home. Less can be more to some people, but less is less to most. I find little truth in this statement: "A Not So Big House feels more spacious than many of its oversized neighbors because it is space with substance, all of it in use every day." -- Susanka. Space is viscerally discernable and less space feels like it! Of course, small house builders use every trick in the book to make the houses appear larger!

Susanka has a section in one of her books comparing housing to automobiles. In a recent online poll (About.com) SUV owners were asked how much they would pay for fuel before trading in gas-guzzlers for subcompacts.

30% said $3.50

8% said $5.00

1% said $6.00

59% said "You'll pry that steering wheel from my cold dead hands"

Building "not so big" could be detrimental to your client"s bottom line, the "savings" tradeoff does not work number-wise, and Susanka"s sweeping statements relating size to quality of space also do not hold up to established architectural theory. She has managed to lure many more people than would normally visit an architect to their offices, but I am afraid many of these folks are becoming disappointed and annoyed when the bottom line becomes evident. The expectations are simply too high based upon this feel-good approach and may cause bitter client/architect/builder relations in the end.

As

it stands, we will build first as large as possible considering budget, then as

good as possible. This is

tradition, at least of recent times. To

be really green about it: cut out the large yards, build three times the density

of the typical suburb or eliminate it completely, and put the savings back into

the quality and features of our homes, externally and internally.

Whether we like detail or space is an economic and cultural

consideration. If any "art" can

be invoked in all of this, so much the better.

Epictetus,

The Manual

Epilogue:

At first the prophet only wished to write a

practical manual on home design, but now bolstered by respectable book sales and

positive feedback from her wide-eyed constituents, the author of this mini-phenom,

picking up on the karma, has launched into a new-wave environmental campaign.

At a recent conference for the , Susanka preached a combination of

home design basics and general observations peppered with feng-shui mysticism

and save the planet epithets. We

were not impressed.

Plan for your Dream Home now. Order ebook here!

< SiteSearch Google -->

THIS JUST IN: (5/8/07)

Workers have long been concerned

about glass ceilings at the office. Now they can wonder if the physical ceiling

is keeping them from their full mental potential. A recent study at the

University of Minnesota suggests that ceiling height affects problem-solving

skills and behavior by priming concepts that encourage certain kinds of brain

processing.

"Priming means a concept gets activated in a person's head," researcher Joan

Meyers-Levy told LiveScience. "When people are in a room with a high ceiling,

they activate the idea of freedom. In a low-ceilinged room, they activate more

constrained, confined concepts."

Either can be good

The concept of freedom promotes

information processing that encourages greater variation in the kinds of

thoughts one has, said Meyers-Levy, professor of marketing at the University of

Minnesota. The concept of confinement promotes more detail-oriented processing.

The study consisted of three tests ranging from anagram puzzles to product

evaluation. In every tested situation a 10-foot ceiling correlated with subject

activity that the researchers interpreted as "freer, more abstract thinking,"

whereas subjects in an 8-foot room were more likely to focus on specifics. In

one test subjects were more critical of a product's design flaws when evaluation

took place in a shorter room. This result could have important implications for

retailers.

Religious experience

The theory that priming a concept in someone's brain might encourage a certain

type of mental processing is not backed up by much evidence from neuroscience or

even experimental psychology. However, one 2002 study found that priming

subjects with either the concept of "self" or that of "other" encourages types

of processing that reflect themes of isolation or unity, respectively.

Meyers-Levy and co-researcher Rui (Juliet) Zhu of the University of British

Columbia formed their new hypothesis after this and other work that has shown

how conceptual priming affects perception and behavior.

The labeling for their somewhat abstract concepts, "freedom" and "confinement,"

comes from a speculative paper on how lofty cathedral ceilings might encourage a

different religious experience from the low ceilings of a modest chapel.

Theirs may be the first empirical study to make use of these terms in describing

concepts that influence behavior. Meyers-Levy and Zhu will publish their results

this August in the Journal of Consumer Research. But Meyers-Levy thinks her

study has wide-reaching applications outside the marketplace.

"Managers should want noticeably higher ceilings for thinking of bold

initiatives. The technicians and accountants might want low ceilings." There

could be consequences in the world of health

care as well, she said. "If you're having surgery done, you would want the

operating room to encourage item-specific processing."

Your comments invited here:

4/ 07/ 05

Hi, I've been a custom home builder in Maine since 1988. The first home I built was my own in 1987, designed by myself after reading books by Charles Wing "From The Ground Up", and Alex Wade "30 Energy-Efficient Houses You Can Build". These books illustrate that the idea of building compact homes for affordability is not a new one.

Many of the rooms in my home were not designed large enough initially. Because it's structurally impossible to make the rooms larger and more functional, I've ended up adding new rooms onto my home two different times. Not only do I still not have enough space to function normally in my home, but I now have odd, small, wasteful spaces left behind. I still heat and maintain these spaces, and the cost of the home initially along with the cost of the additions was more than if I had just built it properly in the first place.

I've been marketing and building higher quality, smaller homes for years, and I can tell you from experience that "Not So Big" (NSB) homes end up being quite expensive and usually over budget. Even after cutting square footage, my customers are usually still faced with the same tough decisions of balancing quality and cost. The space that has been cut out is really not cutting the cost that much, while it is certainly having a detrimental affect on the quality of the spaces in their homes.

I have always counseled my clients that smaller homes cost more per square foot to build, and it is so true. Land, design, permits, groundwork, mechanical systems, kitchen, baths, etc... are basically fixed costs when comparing a 1500 square ft. home to a 3000 square ft. home. Those of us who know the inner costs of construction know the fallacy of the "NSB" approach.

I'll still build the compact homes for those that come to me convinced it is the right thing to do, but MY next home will be very spacious, with a big garage to house my SUV and large sedan. For me, my future "Not So Small" house will be a breath of fresh air and a quality alternative that I can really live in.

Greg Roberts

Design Concepts Company

8/ 01/ 01

The following quote is taken from an article in August's issue of Fast Company and was not submitted to this site:

"I am close to the house, in the cul de sac where it sits even, but no single one stands out as being hers...I finally walk in, however, and it's just a house, like many other nice houses. The entry is not double-height. The refrigerator is a GE Profile, not a Sub-Zero. The screened-in porch is a bit noisy, thanks to the swim club the next over. The master bath has no whirlpool tub, no sexy see-through shower. This, it turns out, is just the way Susanka likes it. In fact, the house is a showcase for her ideas, though it's not exactly showy...Her model home connects most of the ground floor with the cooking, eating, and lounging space all running together.

Ron Lieber, Fast Company

7/ 30/ 01

I am pleased to learn that great thoughts can be conjured in small spaces. (so would be Faulkner, who produced the greatest body of American letters in the shed behind his house; one small window and a bottle of bourbon.)

I am also pleased that the hobbit houses I have designed and crafted, and sold quickly for amounts that smashed the "comps," have appreciated accordingly. One"my favorite, weighing in at 1300SF"recently resold to a couple who called me back to add a screened porch and sauna. Both are MD"s, and could afford twice the house.

I have learned to advise my clients, who are apprehensive about the hobgoblin of RESALE, to kick back and please themselves; that if they do a good job of it, yes, they might narrow the pool of buyers a bit, but they will be rewarded. Conversely, if they do a vanilla job, they will most assuredly get a vanilla return.

But, arguably, this is not reality--this is Takoma Park, MD, AKA "Berkeley East," AKA "The People"s Republic of Takoma," etc. where one can hug a maple or an oak in broad daylight without shame or disapprobation.

I am notsopleased that elsewhere, in the heartland"as John, our shrewd observer notes--we"ve got kiss up to our hedonistic clientele, our bankers, our realtors; that we can"t persuade them that there might be a better balance of scale and quality.

I agree that Susanka"s work parodies her own premise (and I want to hide under my desk when a client walks in packing her books)"but the premise"to build a little better, and a little smarter, even if it means building a little smaller, is fundamentally sound, even if her math is off. It"s in accord with Ruskin, who advised us, that if we can"t afford to use the best stone, then to use the best brick"and if not the best brick, then the best shingle. It"s in accord with the ancients, who said there could be no perfect building without equal measures of "commodity, firmness and delight."

It"s paid off for me.

Alan Abrams

7/ 30/ 01

Its great to hear someone counter-punch the Not so Big boom......The truth is there no evidence to suggest that people are moving on these design principles. Many in the press who latch on to liberal notions of saving the trees & planet have found kinship with Susanka while they read her books in their brand new 6,000 square foot mini-mansion. Yes its popular right now, but I have yet to have someone ask me to minimize the square footage in 'their' dream home. You are completely correct on the dollar cost savings of cutting raw square footage. Unless someone wants to save dollars & square footage by cutting out the kitchen or master bath, merely cutting space will not yeild huge savings. Interesting point about the cost of the avant garde vs. period design, I have found this to be true as well, just because it looks minimal doesnt mean its going to cost minimal.

John, how bout a book from you: 'The Not so Cramped Bungalow', its got a ring to it ehh.

Richard Berry

7/ 30/ 01

Read your comments on Susanka's theory and must agree with you. I

heard

her speak on the subject at a seminar on "Rethinking the House"

"Residential Design and Practice" at Harvard last July.

There were not

a lot of comments or questions from the audience, and during the

breaks

people seemed to be discussing other items. This would tend to agree

with your observation that most were not impressed.

Victor Brighton AIBD

Naples Fl

John,

I've read a Susanka book after my father suggested that his home was "too big," about 3 years ago. My parents live in a home my father designed and built in 1986 (and is a good example of what a bored nuclear engineer does when he decides to change fields). The house is approximately 2,300 SF. It has 3 bedrooms (although one has been converted into a small tv viewing room), a massive living area, decent sized kitchen, and a dining room. The master is of moderate size, and the other bedrooms are smallish about 9x10.

In addition there is a pool house beside the pool in the back that now holds my father's office with a mini-kitchen and bath. The combined floor space is IMHO already "not so big."

So when my father told me that he and my mother were looking at "something around 1200 SF," I was shocked. When he mentioned the "not so big," philosophy I was a little confused. If my parents have any problem it is that the house is too small, and the yard is too big making his mowing chores a hassle (the yard is over an acre). However the house is extremely well designed, energy efficient, etc. By too small I think its only room sizes. Make the bedrooms about 2 feet wider and 2 feet longer, make the master bath bigger, and the kitchen bigger and you have a brilliant house.

So I read Susanka's theory to see if I could understand what my father was getting at.

Then I read your reply to her theory.

I have my own theory:

99% of all homes are designed poorly. Little thought is given to actual USE of a home. Homes today are designed by idiots who have little reason to even be designing a home.

I design Home Theaters for a living, and have been working in the "low voltage," field in Austin, Texas for 2 years now. I've yet to meet an architect who truly impressed me. I've yet to meet a builder who believes that Quality is better than CHEAP. Attention to detail is a marketing term they spit out but have yet to show me they even want to follow thru on it. A $1M dollar home won't even have proper wiring for today's needs because they can't spend $1,000 more on our services. Detail means their profit margin. They just don't care, educating them generally leaves you frustrated. 99% of the time if wiring upgrades are done to actually meet a clients needs, its because the client made the choice not the builder, architect, or designer.

It doesn't matter if its Drees, Toll Brothers, or a custom home builder who builds $1M+ 10,000 SF homes. They don't care about anything but the pocket book.

Austin is filled with new homes that all look the same. Price doesn't matter, it may not be a cookie cutter home, but the custom homes in Austin all seem to be designed with "Mediterranean," motifs. However none of them do a good job of ever capturing a true style and seem to be extremely poor mismatches of every Mediterranean design out there.

Plus there is the layouts of these homes. McMansion is a good term, because these homes seem to have been designed by Grimace that big purple monster that loves shakes. There just doesn't seem to be any thought put into these giant homes. In the last two years I've been in about 200+ of the biggest new homes in Austin. To say that any of them are well thought out would be a lie. I half believe that the homes were designed by the blind.

Just yesterday I dropped by and looked at the blueprints for a new client. His home is being designed by Austin's biggest custom home architectural firm. The client asked for a "dedicated theater room," and what did I get to look at?

An OCTAGON with one half of it windows, big giant windows. "Theater rooms are never open, they lack real lighting techniques that offer a room," at that point I interupted and after 2 years lost my temper. I told the architect he was an idiot. That he should have any permits or licenses taken from him, and that he shouldn't be designing homes. Lets forget that there couldn't possibly be a worse shape for room acoustics than an octagon. What about the windows? Theaters need to be dark to function.

This isn't uncommon. I've seen round theaters, square, and yes other octagons. It is routine in this town to see a blue print or worse a finished home where the client wants his "media room," that is filled with windows. Some of them big bay windows overlooking amazing hill country and lake views. These are even called "media room," in the blue prints.

How hard is it for an architect to research a room he is designing? Certainly somewhere there must be architectural documentation on room acoustics? Certainly the same could be said for theater rooms needing a total lack of natural light?

If Architects can't get 1 room right, how do you expect them to do a house big or small right? I'd fully understand if they'd never designed one before. Yet I can't forgive them for not researching before designing. There is no excuse for this level of absurdity. Most architects I've found are more interested in their vision than what a room is for.

The idea of smaller is better for design is preposterous. How exactly are these architects and designers going to get a home right at 1,500 SF if they can't do it right at 15,000 SF? My guess would be that you'd get a cramped home with no real chance at it ever being "lively."

I've been in some Frank Lloyd Wright homes that were small in comparison to what most people live in today. I'd say that those Wright designed homes were far more livable.

So the problem isn't in the size of the home. Its the guy designing the house. I'd love to think that a properly designed smaller house would be better than a poorly designed larger house. The real problem is good luck in finding the person to design your smaller well thought out house. Your options will likely be between Grimace, Ronald, the McBurglar and Stevie Wonder.

So you might as well go big, because even a blind pig can find an acorn. So chances are better with more rooms to design, that they might just get one right on a big house.

Oh any my parents? Three years later they live in the same house. After looking at every builder's small spec homes in the areas they would consider moving to, they couldn't find a solution.

Size doesn't matter. That is the bottom line. The architect matters. Finding the right architect will likely take ages, but the search is well worth it. Then of course you have to find the builder.....

-Jake, 3/28/06

May I just say that, after 9 years as a new home sales agent/broker,

"Jake" (3/28/06) is absolutely right in asserting that the problem lies

with faulty design. However, I feel that the real problem is that

there is so much wasted space in home designs. I am an admirer of Ms.

Susanka because she led the charge against space for the sake of space.

Certainly, some space is inherently valuable to one's perception of the

space even if it has no apparent function. But there ARE wasted rooms

in today's homes. Formal dining rooms and/or formal living rooms are

used by most people now perhaps once or twice a year. Why spend

$15,000-20,000 more on such an infrequently used room? There are other,

more

sensible ways to separate living spaces from more public spaces.

Typically, though, one rarely enters one's home through the front door

these

days and for those times when the adults are greeting and entertaining

guests (if one lives in the midwest, as my clients do) one sends

the children to one's basement for the more "rustic activities" or to

a playroom created by expanding the relatively inexpensive space over

the garage. Additionally, often designs just waste space in general.

I have personally been able to cut 200-250 square feet from some

designs without negatively impacting room size or flow. And, when one is

planning to use high-quality finish materials, those extra square feet

can translate to a lot of extra cost. Cutting just a few feet from a

room can make the difference in whether one uses the species of hardwood

one prefers or "settles" for something less expensive. Therefore, I

agree with Ms. Susanka that less can be more and that more is often less.

Carol Bronder

St. Paul, Minnesota 4 06 06

This all depends on how you were brought up (Susanka in small apartments in England; me too) and accustomed to.

More space means more flexibility. If you have more money, you will want more house.

If one does not have formal living and dining rooms, then opening into a family room means that it has to be kept up.

In the south with no basements, having small children around means coming into a house with toys strewn in front of you or in SS's case: a wall to hide that messy space. Then the house feels confined. [Having a basement is a trump card for the midwest house and that extra space should be factored into the whole. Consider the 'flex' aspect of a basement; just about anything goes: Den, Exercise, Office, Play Room, storage, etc. -- so that the typically Not So Big House, has cheated space below... at least in the Midwest or north of the frost line.]

Most builders in the south have taken up the 'California model', which is to see through the house immediately upon entering. You can have a small glass wall immediately at foyer face, or see into a room and out into the back yard. In Florida, we often locate a small Living room there. Then the house is picture perfect, even though that room may not be 'used' as much as a Family or Great Room. Due to narrow lot conditions, the Living and Dining are often diagonally set at Foyer, then an archway takes you into Family/Breakfast/Kitchen, which has been the base model layout for the last 20 years in entry level houses.

Yankees, who are tired of climbing stairs, living in boxes, etc. bring down their heirlooms and fill the formal Living and Dining rooms, love the vaulted spaces, and large windows, and never look back.

Formal spaces allow one to get away from the hobbit hole experience of a small house.

We can all live in double wides as far as I am concerned, but space, cheap space, allows you to breathe and has a psychological positive. Gargantuan space, or ill proportioned space, is questionable, but I would take it over the over planned, inflexible fixed rooms with cubbies all around, built ins, and tight quarters. To take this 'extra' or cheap leftover space and think you can guild your remaining hobbit hole is a specious argument.

John Henry , 4/06/06

I would like to respond to yours (above) in part. "If one does not have formal living and dining rooms, then opening into a family room means that it has to be kept up." While this is true, I have found that when one has company over they must invariably also clean up their "informal spaces", since the plans these days open the kitchen to an informal dining area and to the family room and "company" likes to hang out in the kitchen with the cook.

Our plans here often include an office open to the foyer and an archway/hallway which leads you into the "rear space". There may or may not be a formal dining room on the other side of the foyer. Or, there may be hallway to a mud room and powder room. So one does not have to have a formal living room and dining room to create a "public" entrance that screens the rest of the house.

Many of our plans evoke the California design allowing you to see through out across the back, a nice feature when there is a view. Windows are often across the entire rear of the house, allowing you to appreciate the view from most if not all of the main floor living space.

Carol 4/07/06

I've been looking at your website and truly appreciate your response to the Not So Big House. I completely agree with everything you write. The fact that I've gotten responses to my home from Germany, England and both coasts of the US, indicate that people respond greatly to the overall size of my home at nearly 5,000 sq ft, to include the spacious ceiling height of +10 feet. People love the large rooms and are rather stunned at how large it feels when they enter the foyer.

And, of course, the fact that it's priced at $149,000 is an huge draw...it's incredibly cheap per sq foot. And, I have a newer roof, furnace, etc, etc, etc.

The only negative comment I've heard back from the realtors is the concern for heating my home. Given that I spent $2100 last year and keep my home a comfy 72 degrees and the increase was actually due to fuel price increases not consumption, I don't think it's a valid concern. But, there isn't as great an appreciation here for large, vintage homes as there is from people outside of the Midwest.

Gloria 7/28/06

To contact Architect: johnhenryarchitect@gmail.com

Creating the American Luxury Home Available now on CD- rom. (click below left) This is a history of the luxury home with sections on working with an architect and builder, style, modern and traditional approaches, etc. Also, companion volume: Dream Home Design Questionnaire and Planning Kit (click right below, available as PDF file via email)

Chateau des Reves:

click image above for exclusive video of interior spaceUltra Luxury Custom Homes, Villas and Estates by design

Copyright 1999/2000/2001 by John Henry Design International, Inc. All rights reserved.

Republication or re-dissemination of this site's content is expressly prohibited without the written permission of John Henry Design International, Inc.

John Henry Architect

MasterWorks Design International, Inc.

7491 Conroy Road

Orlando Florida 32835

TEL: 407 421 6647

EMAIL: johnhenryarchitect@gmail.com

Custom Home Design Services » Custom Home Remodeling » Luxury Home Interior Design Services » Custom Home Design Intro Offer »

About the Architect » Contact John Henry » Home Design Fee Schedule » Period Style House Design » How to Design Historic Mansions » Architect's Blog » Home Planner Ebook » Bibliography » Boxy But Good » Not So Big? Not So Smart »